Of all the buildings and locations on and around the battlefield of Waterloo, none were better known to Jan and I than Hougoumont. I had read so many stories about the heroic defence, seen so many drawings and photographs, that I felt I knew it well - even though I had never been there before. So to actually walk in the grounds of Hougoumont was an experience we were not to forget.

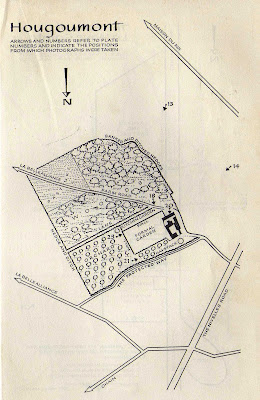

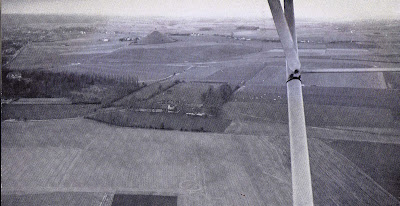

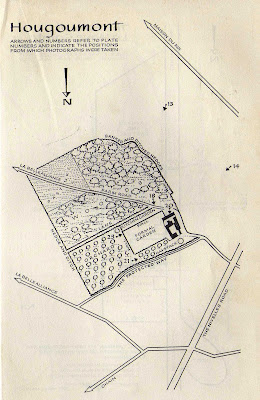

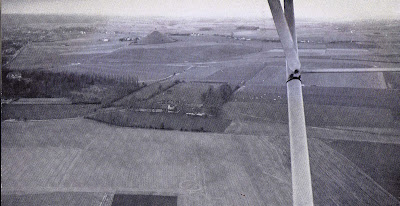

But before we recall the visit itself, lets just remind ourselves where Hougoumont is, and why it was so important. These two aerial photographs help us to do so. The one above was taken from 14 in the plan. You will see that this was the direction of the French attack. You can also see how close the farm is to the Lion monument, which marks Wellingtons right flank. Hougoumont is not as close to the allied positions, but it does protect his right flank. And of course because it is slightly further from the allied line, it was more difficult to support, reinforce and resupply.

The second aerial photograph gives an even better impression of the farm and garden. The "covered way" is a sunken road which gave some shelter to reinforcements or resupply vehicles moving to the farm. As this road was nearest to the allied line, it was commanded by the allied artillery and dangerous for the French to approach.

Although the farm was surrounded by the French during the battle, not a single Frenchman managed to enter either the farm complex or the garden and survive - except as a prisoner.

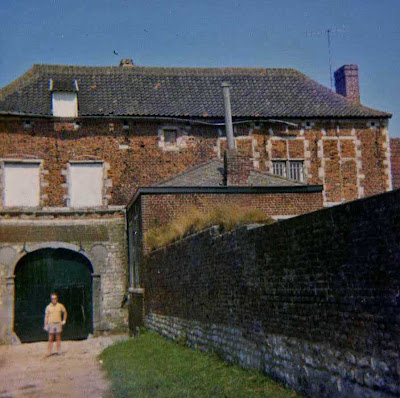

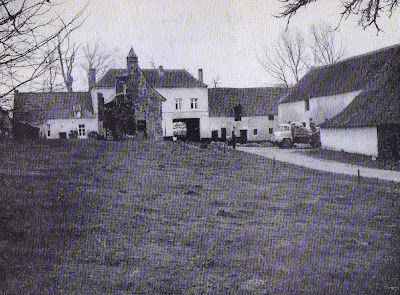

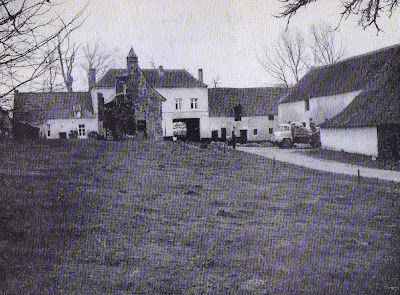

This is the view of Hougoumont which most of the attacking lines of French infantry would have seen. However at the time of the battle there would have had to pass through an extensive woods to reach this point.

I have a large poster of this famous painting in my wargames room, of the hand to hand fighting for possession of the woods to the south of the farm.

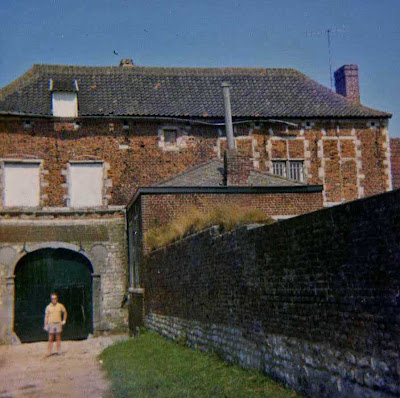

In preparation for our visit to Hougoumont we had read Jac Wellers "Wellington at Waterloo", in which he confirms that visitors are welcome in the courtyard, the ruins of the chapel, the garden and through the passage to the south beneath the first floor of the farmers house. Given that this is a working farm, I think this is very generous of the resident farmer.

It was quite an experience to stand in front of the very door which played such an important part in the battle. We sat by the wall and read an extract from our second reference book David Howarth's "Waterloo, A Near Run Thing". This is a collection of first hand accounts of various events of the battle. Unfortunately I no longer have my copy, so I can't quote from it. However I clearly remember reading about an English skirmisher who was so involved in the fighting in the woods that he failed to realise that his colleagues had withdrawn inside the farm. When he reached the gate, he found it locked. He recounts how a French skirmisher took careful aim at him, fired, but missed. We read this account right by the door he found locked on the wrong side on that memorable day

As we sat there, the farmer came out on his tractor. He gave us a friendly nod and went on his way. So we felt quite encouraged to fully explore the farm and gardens.

Another famous painting of the fighting for the southern gate. For me this one captures what it must have been like to come forwards and batter against this door time and time again.

We walked around the outside of the garden wall. Its much higher than I had imagined, and it was interesting to read that the defenders built wooden platforms so that they could fire over the wall at the attacking French. They also knocked loop holes in the wall, which could still be seen. We paused to read an account of how the French grasped hold of the muskets and tried to pull them through the loop holes.

We walked around the farm to the northern gate, or rather to the gap in the wall where the northern gate would once have stood. This was the scene of another famous episode of the battle. The garrison had left this gate closed and barred, but not barricaded, so that they could receive reinforcements and ammunition from the ridge.

"A giant French leiutenant seized an axe from one of his pioneers and weakened the bar where it was exposed between the doors. He then led a charge which crushed the doors inward breaking the bar. In an instant, many French rushed into the courtyard. But (Colonel) Macdonnel himself and several officers and men closed the gates by main strength, replaced the bar and killed or incapacitated every enemy soldier inside, probably helped by musket fire from the surrounding buildings".

Wellington was later to say that Colonel Macdonnel (commander of the garrison) was the bravest man at Waterloo, and that his action in closing the gate was the most important single action contributing to winning the battle.

To sit in the courtyard entrance and read this account was thrilling indeed.

This photographs was taken from the north gate looking across the courtyard towards the chapel and the south gate. This was the scene of another epic action. "The buildings were set on fire by French howitzer shells, but resistance continued unabated, since a large part of the actual fortfied area was in the open behind bare walls."

Wellington sent a note pencilled on goatskin to Macdonell which read:

"I see that the fire has communicated from the hay stack to the roof of the chateau. You must however still keep your men in those parts to which the fire does not reach. Take care that no men are lost by the falling in of the roof or floors. After they will have fallen in occupy the ruined walls inside of the garden, particularly if it should be possible for the enemy to pass through the embers to the inside of the house".

Only a few days earlier we had seen this very message, handwritten in pencil by the great man himself, in the Wellington HQ museum in the village of Waterloo.

The chapel was amongst the buildings which caught fire. It was being used to shelter wounded soldiers, both French and English. Many perished as they were unable to drag themselves out of the building. There is a wooden cross on the wall of which only the feet are burned, the rest survived.

A very sad place to stand and consider how terrible it must have been to perish in such a dreadful way. I recall reading about a guardsman who was fighting in the nearby farm. His brother had been injured earlier, and placed in the chapel. When he saw that the chapel was on fire he asked, and received, permission to leave his post and move his brother out of the chapel. As soon as he had done so he returned to his post in the farm.

This photograph was taken from the top of the garden wall and is number 23 in the diagram above. Area A is where the French infantry tried to pull the muskets through the loop holes. B is the farmers house. C the chapel. This garden was the scene of some of the most determined fighting of the whole battle. The defenders fired over the wall, and through the loopholes, and bayonet any Frenchman brave enough to try to climb of the wall.

Corner of the south and east garden wall. The bricked-up loopholes show clearly in the right foreground section. Further to the left are some stone lined loopholes, still open, made when the wall was built.

Our second, well thumbed, guide to the battle. Jac Weller is great for a general overview of the battle, and the sequence of events. But David Howarth really brings it all to life with the actual words of men who took part in the battle. My favourite memory of visiting Waterloo is of sitting in the garden, eating a picnic lunch and reading from "Waterloo, A Near Run Thing".

Jan is standing near a monument to the French who died at Hougoumont. Srange place to put it. There were many casualties in the general area, but I believe no French soldier entered the garden, except possibly as a prisoner.

There are also two graves in the garden covered by stone slabs. One is where Captain Blackman of the Coldstreamers was buried on the day after the battle. The second is Sergeant Major Edward Cotton of the 7th Hussars. He died at Waterloo in 1849, a wealthy man after many years as a professional battlefield guide.